A guide to digital product design roles, cheat sheet included

Today, we have people identifying themselves as UI, UX, brand, interaction, visual, product, service, insert-obscure-reference-here designers. There seems to be a need for highlighting all these specializations within what is essentially a single job title — designer.

So how do we know who does what, and which designer to hire?

Activities required by the digital product design process

In order to make this simple and understandable to the layman, let’s say that the digital product design process assumes the following activities:

Key activities

Understanding businesses

These are processes through which designers learn about the businesses and users they serve, as well as the entire problem space. This encompasses everything from interviewing stakeholders and users, making sense of analytics, studying competition, running workshops, etc.

Understanding users

This is the part of the design process focused on creating ways to satisfy user and business needs by identifying challenges, proposing hypotheses, defining user flows, and making wireframes.

Interaction design

By defining how things like pages, screens, and elements react and relate to each other, designers are able to make usable, functional flowing experiences which “make sense” to users even without prior usage.

Communication

Verbal or visual, design’s ultimate goal is to communicate with the subject. Words are powerful, and the less of them there are, the more responsible designers need to be with them. A lot of communication happens non-verbally, and this is where it’s important to be able to command things like form, color, typography, hierarchy, density, etc.

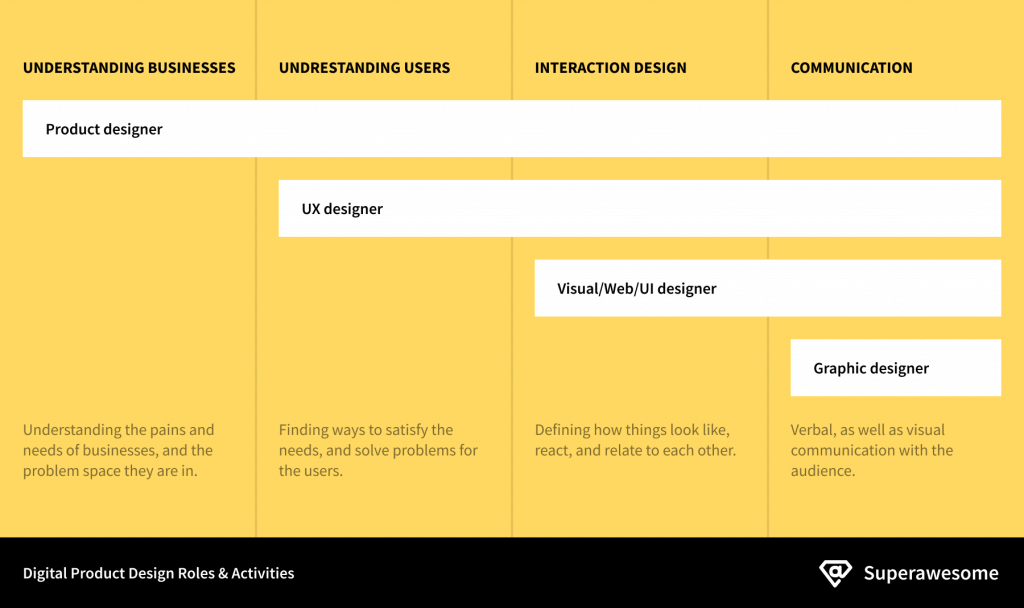

Designer roles required by the digital design process

Now, as far as roles are concerned, going along the same vein let’s limit them to the activities required by the digital product design process — so scoping our chart to this design branch only — going from narrow to broad.

Roles

Graphic designer

Responsible for producing graphic assets from a specification, including icons, illustrations, branding assets, photography edits, etc.

Visual/Web/UI designer

Responsible for defining how things look like, and producing visual assets (i.e. screens) used for digital products like apps and websites. These usually come in the form of “mockups” or “comps” (as in “compositions”) where each screen that the user is able to interact with is delivered as an image that the designer produces as a specification for the developers.

UX designer

Responsible for understanding how digital products solve user problems and meet their needs, as well as defining how different elements of pages and screens operate in this case, not how they look like.

Digital product designer

Responsible for aligning user needs with business goals, and making a functional digital product. Their job consists of taking both stakeholders’ and the users’ interests, and marrying them together in a whole which brings value to both parties.

Product designers work from a business need or problem, and transform them into opportunities. The output of their work is not necessarily a solid deliverable, and is often realized through other people’s work.

Now that we have this basic understanding of the requirements we need to satisfy in order to facilitate .a digital product design process, we can create a handy reference chart!

As you can see, there are design roles that actually encompass other design roles, product design being sort of like an umbrella role. Even though it’s important to note that not all product designers actually partake in what are commonly considered “design activities” i.e. graphic and UI design, many of them do go full circle.

Lately a role called “service design” has appeared, and it’s scoped even broader, extending its touch-points beyond the product itself, but I have left this out intentionally as I feel it is beyond the scope of this article.

So what’s the difference?

It’s really important to be able to tell whether you need a specific kind of a designer for your project. Clients so often come to us requesting “visual” design services — because this is what they consider “design” — when in fact they need several designers, or a one-man-show type product designer.

And in case you’re wondering, the difference between e.g. a UI designer, and a product designer can be easily described using a simple analogy.

Imagine a situation where a scientist is explaining a phenomenon taking place on a massive space and time scale. This thing is something no one could have ever possibly witnessed. The scientist is explaining this to a person whose task is to visualize it, in other words to describe it graphically by producing a deliverable like a painting or a picture, an animated video, or an illustration for a magazine…

In this dynamic the scientist is the stakeholder with domain knowledge, and the person tasked with the visualization is the UI designer. Since the scientist has done all the heavy lifting of understanding the phenomenon, and they are able to explain it so the other person can fully understand it, possibly providing examples and analogies along the way — to provide a brief, in design terms — the person with the task of visualizing it only needs to execute based on that which is explained. Hence, hiring someone with a broader skillset would not be necessary.

If you are a stakeholder with domain knowledge you probably need to hire someone for the execution only, provided you are able to transfer that knowledge to this person.

However, consider the situation where the scientist is replaced with a stakeholder that doesn’t understand the matter, they are only aware of the phenomenon. They can’t explain it, they just know there’s something. In this case they need a person that is able to take that which is known at that time, work to completely understand what’s going on, in order to be able to produce the visualization, educating the stakeholder along the way.

This time, the stakeholder is coming in with nothing more than a problem, and needs a person with a broad enough skill set, capable of not only executing on a very specifically defined task, but solving the entire problem. This person is a product designer.

If you are a stakeholder without or with limited knowledge of the problem space, you need a product designer, and possibly other designers depending on the product designer’s abilities.

Complexity necessitates specialization — a little bit of history

The design industry was fine, and its roles well defined just a couple of decades ago. Design was a part of advertising and marketing, and its use and place were well known within these industries.

I personally see the identity crisis starting about the time a designer could find full time work, doing only UI design — designing for screens — which means right about when digital products appeared. Up until this point the word “designer” was simply synonymous with “graphic designer”.

From this point on, designers working on digital products exclusively started identifying themselves as “web designers” in order to distance themselves from the traditional medium they hail from, and let the world know that even though their profession is rooted in graphic design, their jobs are so different that it requires its own title respectfully.

On one hand I can understand this need. People want to communicate very clearly what they do without creating false expectations. Someone who is heavy on the research and strategy doesn’t want their potential employer or client to think they can do branding just as well — or at all for that matter.

The field of design has grown so much with the advances in technology, and when we take into consideration that designers finally have a seat at the table — or do they? — we are forced to differentiate and let the world know that it’s highly unlikely that one person alone can do it all.

So while I do agree with this sentiment of niching-out, I do take issue with is the naming aspect. Imagine architects — architecture being a highly regulated field, mind you — all of a sudden not being architects, but “facade architects”, or “column architects”. What I’m trying to say is, it’s OK to have strengths, it’s OK to be T-shaped, there’s just no need to scope yourself so tight that you niche yourself out of business. There’s just no need for a role name to be so exclusive.

If this trend continues we’re going to make people think they need a different person for every different activity in the design process!

Design generalists

While this segmentation has been going on, a special strain of a designer formed as a counterculture — the design unicorn that said no to specialization, and decided to focus on doing it all. Vision, strategy, UX, UI, branding, all of it.

These guys are your typical one-man-show types, and as the name implies consider yourself extremely lucky if you find one, let alone being able to afford to bring one on.

Who’s getting the short end?

The biggest problem that I see here is not with the designers, as they — generally — know what they are talking about. It’s the clients, and the employers that are getting the short end of the stick. How can we expect them to know whom they should hire? They are not the experts.

This is a lot of extra work for the client, forcing them to make decisions they may not be equipped to make. Does this project require engaging three different people, or is there one person that can get the job done?

“This candidate says they are an ‘interaction designer and a visual storyteller’, but we’re not sure if we should get in touch, we just need a website. Also, do we need a developer as well?”

Anyone tasked with a simple task of creating a company website has had this cross their mind at least once.

Segmentation brings another problem to the table apart from confusion, and that’s increased cost through project management, and knowledge sharing. It’s a different ball game keeping a team of six in the loop, vs a team of three. Bring remote work into the picture and you have your work cut out for you.

This is at least one of the reasons why senior positions (i.e. generalists) are so popular with small companies. These companies often don’t have the necessary resources for project management, or established processes in place, so having people that are not just executors of specifications is really valuable.

Having self-managed people that are able to go in depth on their own in order to solve problems, often gives you a huge market advantage.

We are all designers, after all

We’re all still just designers, but the amount of things that require design today is massive, hence the amount of stuff needed to produce design across different mediums and platforms has grown accordingly. Design is no longer recognized as only the veneer or a finishing touch added as an afterthought (how things look), but a part of the process which helps people make better things (how things look, and work).

It’s not realistic to expect all designers to be competent in all these new aspects of design — hence the specialization — but it’s wise to be educated about which design problems different projects require, and which designers are most suited to solve them if you are the type of person likely to require design services, or work with designers.

Perhaps our biggest fault is the lack of authority in the design industry. There is no milestone one reaches in order to earn a title, so we make them up as we go along.

Saying you are a product designer just because it’s the new hot thing, when in fact you draw UIs and can stitch them up together, is not doing anybody any favors. You may aspire to be one, but please be sensible about it.

We need to be honest, up-front and precise regarding our specialization, without sounding obscure and esoteric. We need to do a better job of communicating and presenting our work, so people don’t have to guess what it is that we do.

Maybe then titles and roles won’t matter as much.

What's this?

You are reading his blog.